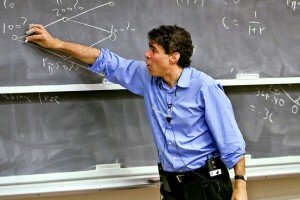

Last year, MIT Sloan School of Management published a study performed by Professor and head of MIT’s Entrepreneurship program Ed Roberts (David Sarnoff Professor of Management of Technology, Founder/Chair, MIT Entrepreneurship Center), and Professor Charles Eesley (Assistant Professor in the Entrepreneurship Group at Stanford University). The study demonstrates MIT’s entrepreneurial impact, which may be typical of several of the country’s major universities but likely is tops.

Last year, MIT Sloan School of Management published a study performed by Professor and head of MIT’s Entrepreneurship program Ed Roberts (David Sarnoff Professor of Management of Technology, Founder/Chair, MIT Entrepreneurship Center), and Professor Charles Eesley (Assistant Professor in the Entrepreneurship Group at Stanford University). The study demonstrates MIT’s entrepreneurial impact, which may be typical of several of the country’s major universities but likely is tops.

This discussion summarizes an exhaustive study of MIT graduates’ entrepreneurial record; it was limited to those who founded companies, not including entrepreneurially motivated professionals who answer to their corporate responsibilities rather than to start their own business! But the points presented in the study implicitly suggest (if not helping to define) the rapid growth in entrepreneurship by university graduates. Although as mentioned it provides little data about E. trends in the office, we certainly recognize the many corporations which have been including E. factors in their promotion criteria, and their reliance on outside entrepreneurs for assistance.

The MIT study concluded that research and technology-intensive universities via their entrepreneurial spin-offs have had a dramatic impact on the economy of the United States: MIT is undoubtedly at or near the forefront of this trend; extrapolation of the underlying survey data shows 25,800 currently active companies founded by MIT alumni that employ about 3.3 million people and generate annual world revenues of $2 trillion, producing the equivalent of the eleventh-largest economy in the world!

In addition the study demonstrates that a higher percentage of graduates pursuing new ventures, emerge out of each successive MIT graduating class, in other words the trend is an acceleration of entrepreneurial activities, and entrepreneurial graduates are starting their first companies sooner (and at earlier ages). Also, the number of companies founded per MIT alumnus has also been increasing therefore generating increasing economic impact per graduate.

The type of firms founded by MIT alumni may reflect the thrust of the school: these new companies are frequently knowledge-based in software, biotech, manufacturing or consulting (generally in the architectural, business, and engineering spheres). Because most represent advanced technologies and generally sell to interstate and world markets, they may have a disproportionate importance to their local economies; for example, the statistics show that they employ higher-skilled (and therefore higher-paid) employees, nevertheless their global revenues per employee are far greater than the revenues produced by the average American company.

The overall MIT entrepreneurial ecosystem rests on its long history (it has developed thirty different entrepreneurship courses). Students of entrepreneurship study together and in teams, and in fact, aspiring entrepreneurs might learn a lesson from this: where possible, connect with others of like mind, and join focused entrepreneurial clubs and organizations…this should enhance your benefits from the “networking effect”.

In 2000, MIT’s “Venture Mentoring Service” was begun to help any MIT-related individual (anyone who was a student, staff, or faculty member…. even an alumnus contemplating a start-up). The service has already seen more than eighty-eight companies formed. To emulate this, those who are ambitious with entrepreneurial ambitions might mimic IBM’s program, and reach out…e.g. to actively initiate connections with others who might help in designing and promoting new ideas.

Does age correlate with when one’s entrepreneurial tendencies emerge? The MIT study showed that the more recent entrepreneurial firms include many which evolved from relatively younger age brackets! But note that entrepreneurs have also emerged from the late forties and fifties age brackets, and MIT believes that individuals can “re-invent” themselves at virtually any age (at least to some degree), in the direction of applying entrepreneurial characteristics which will stand them well in life (I’m 75 years young and still playing with new business ideas).

The average MIT alumni entrepreneur has founded 2.07 companies over his/her lifetime and interestingly if not obviously, repeat entrepreneurs seem to have a greater economic impact relative to the overall number of entrepreneurs studied.

In its study, MIT discovered findings with regard to both competitive edge, and obstacles to success. Interestingly, it concludes that successes and obstacles apply in the office as well as at start-ups (and elsewhere as well), by asking MIT alumni entrepreneurs to rank what seemed vital to their obtaining competitive advantage: the responses re success, in ranked order: (1) superior performance, (2) customer service/ responsiveness, (3) employee enthusiasm, (4) management expertise, and (5) innovation/new technology—all ahead of product price (if a startup has a cutting-edge product with outstanding performance and good customer service, it can reasonably charge a premium). In other words as I interpret it, innovation and new technology was ranked last by entrepreneurs! I can only interpret that to mean that a good idea does not see daylight without other fundamental business attributes. And several issues were left out, such as appropriate financing.

And with regard to the regular employees in an office (not the founder of a start-up), a lesson from the survey might be that superior performance (which actually embraces customer service, responsiveness, enthusiasm, expertise, and last but not least, innovation, means that entrepreneurship can be practiced everywhere!

Most MIT alumni companies started with funds from the founder’s personal savings or by re-investing cash flow. Entrepreneurs’ dependence on personal, family, friends and informal investors, is not just an MIT-related phenomenon, but seems to have been true for entrepreneurs in the United States and globally; but aside from self-funding, VCs (venture capitalists) are obviously important to many firms. Nevertheless, in none of these cases were VCs and other alternate sources more important at the outset than the founders’ own savings! But VCs and other external sources did become important for companies that grew to fifty or more employees. I wish to note that this does not necessarily correlate with my own limited experience: ‘angels’ and VCs typically enter the picture earlier or later (if at all), and with greater or lesser investment size, let alone easier or tougher terms, based upon general economic conditions and the financial strength of the investing communities community. This should be obvious, so the lesson to be learned is that entrepreneurial success is to some extent dependent upon economic conditions, and must be taken into account by all those with great new ideas.

A reasonable question might be: can individuals who have not benefited from intensive and appropriate scholastic involvement, also share in the opportunities which formal preparation would have enabled? The answer is presumed to be yes, but with obvious limitations; I have not seen statistics re this point- it’s likely a subjective judgment based upon many variables. My own view is that entrepreneurial talent assists one’s success in a general sense, regardless of whether an explicit company is formed as a result. But for those with talents which are viewed as entrepreneurial (and note that these talents can be learned), the chances of ending up with greater success, perhaps leading to the founding of new and innovative organizations, increase.

Returning to what MIT ‘s role has been in nurturing entrepreneurism: it has clearly been immense, but only for those relatively few who were lucky enough to experience its influence directly. Of course, MIT is not alone. But the closest parallel I can find is not another university, but Israel’s military. Explicitly due to its practices, it has produced a giant wave of entrepreneurship; Israel has a total population much smaller than New York City’s, but has produced more successful ventures per capita than any country in the world, by far. But that’s another story.

6 Comments