Soundview Part 2: The later years

Banking relationships at most of the other Wall Street tech boutiques like Montgomery Securities were more important than research, which was often seen as creating a conflict. But Soundview’s concentration on research and research culture was as strong as it had been at Gartner Group even though it paid less than Wall Street’s elevated salaries and bonuses (albeit considerably more than Gartner). Unlike most Wall Street firms whose tech analysts were MBAs instead of electrical engineers, Soundview brought to the table both its its own analysts who had actually worked for tech companies and knew what they were talking about, plus the Gartner Inc. analyst relationships as well! While it occasionally lost a professional, it retained most analysts, sales people and traders, by arguably offering a more satisfying culture and lifestyle than Wall Street professionals enjoyed, plus its stock ownership for all (Wall Street equity at the time was generally restricted to partners).

Banking relationships at most of the other Wall Street tech boutiques like Montgomery Securities were more important than research, which was often seen as creating a conflict. But Soundview’s concentration on research and research culture was as strong as it had been at Gartner Group even though it paid less than Wall Street’s elevated salaries and bonuses (albeit considerably more than Gartner). Unlike most Wall Street firms whose tech analysts were MBAs instead of electrical engineers, Soundview brought to the table both its its own analysts who had actually worked for tech companies and knew what they were talking about, plus the Gartner Inc. analyst relationships as well! While it occasionally lost a professional, it retained most analysts, sales people and traders, by arguably offering a more satisfying culture and lifestyle than Wall Street professionals enjoyed, plus its stock ownership for all (Wall Street equity at the time was generally restricted to partners).

Fortunately the years from 1991 to 1998 represented one great cycle for stock market investors, and of course for ‘producers’ working for Wall Street sell-side firms, including Soundview! The company grew from about $6 million in ’91, to $10M, to $18M, to $32M, to $50M, to roughly $80M in ’96 (its book value was of course lower). In 1997 Jamie Townsend left the firm for family reasons, and Russ Crabs who began his Gartner career as my executive assistant (as had Scott Smith), become Soundview’s Director of Research and soon after was elevated to be Soundview’s CEO! By 1999, Soundview had 30 analysts, its revenues were well over $120 million, and it opened a West Coast office.

Soundview’s book value increased at least as rapidly as its revenues, especially as its trading capability expanded. Trading was a key to growth as Institutional clients such as banks, insurance firms, and foundations paid all of their research suppliers strictly via their trading desks; for example giant Morgan Stanley Research would pay relatively tiny Soundview by giving it a growing portion of its “buy” and “sell” execution orders which in turn generated commissions.

In 1998, Russ Crabs became Soundview’s President, and soon reportedly responded to a large Wall Street firm which had followed Soundview’s progress and was tempted to possibly acquire it. Russ had earlier consolidated his power (now owning about 13% of the firm), and began to more seriously consider selling the business. By 1999 word evidently got out, Raymond James expressed concrete interest and it’s rumored that J.P. Morgan spoke about or offered $250 million cash to acquire the firm, but this initiative was rejected!

By this time, a firm called Wit Capital had been formed, specializing in investment banking with various innovative strategies, for example in allowing small investors to participate more readily in deals. In 1999 not only did Goldman Sachs buy 22% of the Wit firm (Nasdaq: WITC) but it attracted three heavyweights to lead its operations, and went public itself as “Wit Capital Group” with its stock rising over 60% on the first day of trading which only increased its hunger for growth!

Very soon Wit offered and Soundview accepted a buyout managed by Goldman Sachs for about $320 million (a big multiple of Soundview’s book value) plus some cash to pay key employees something up-front. However, around $300 million of this was in Wit stock, and moreover the stock was locked up for three years! Russ Crabs was to become a board member of the new Wit Soundview, but did he previously sufficiently study Wit’s history, market position and prospects? Did the Goldman Sachs connection sway him positively? Did he counsel with his senior partners in-depth? Who did he counsel with?

The deal closed and Soundview employees felt they had hit the jackpot! It now had a run rate of $150 million or so and was undoubtedly the largest and no doubt the best investment research group focused on technology across all of Wall Street, the top experts covering the vast number of vendors and their markets in telecom, computing hardware/software, and infrastructure including the early Internet. And Goldman Sachs was an investor (for the time being at least)!

Wit stock jumped a full 28 percent on the Monday after Wit announced it will buy SoundView Technology Group and said that the research of SoundView’s 30 analysts which was previously available only to institutional investors would now be available to individual investors via the Internet! Wit also pointed out that it was acquiring access to all of Soundview’s 450 institutional clients (with firms like Fidelity paying over $1M annually) putting it in a strong position for IPO underwriting, and again emphasized that banking was the main theoretical driver of the acquisition!

But unfortunately Soundview and Wit were both becoming different companies. Russ, my ex-assistant and Soundview CEO was quoted “Wit Capital intends to leverage the equity in the SoundView name”; but I’m told that on the day the deal closed, Ron Readmond (co-CEO of Wit Capital) appeared on CNBC, indicating that the SoundView name would likely be dropped at some point – given the predominance of the Wit brand!? Of course this never happened (later in 2002 well after the height of the market collapse, the combined company changed its name again to SoundView Technology Group, dropping the Wit name and underscoring that the deal had been a disaster for Soundview because of Wit’s weakness which could only claim a vision, its “on-line” strategy). In fact, without Soundview, Wit would undoubtedly have had to declare bankruptcy.

Soundview was encouraged to shift its power from research to banking, and it was continuing to hiring bankers en mass! Is that what leveraging Soundview’s name meant? Russ had negotiated the Wit deal but left the firm two years after the sale in 2001 and he was far from the only one leaving, as Soundview people were quitting daily (they watched Wit’s prospects deteriorating, its stock collapsing so very soon after the acquisition, dropping over three years from $22 to $11 to $2 per share!) As the Soundview employees watched Wit’s stock decline, their 3-year lock-up on WIT stock prevented its sale, and thus erased much of what they thought their net worth to be, just months before!

By October 2003, Soundview with very few of its former employees remaining was sold to the giant broker Schwab, and about a year later the huge Schwab finally recognized and acknowledged that the Soundview it had acquired was not the Soundview of old and in turn sold what little was left to UBS, essentially for its trading (order-flow) operation.

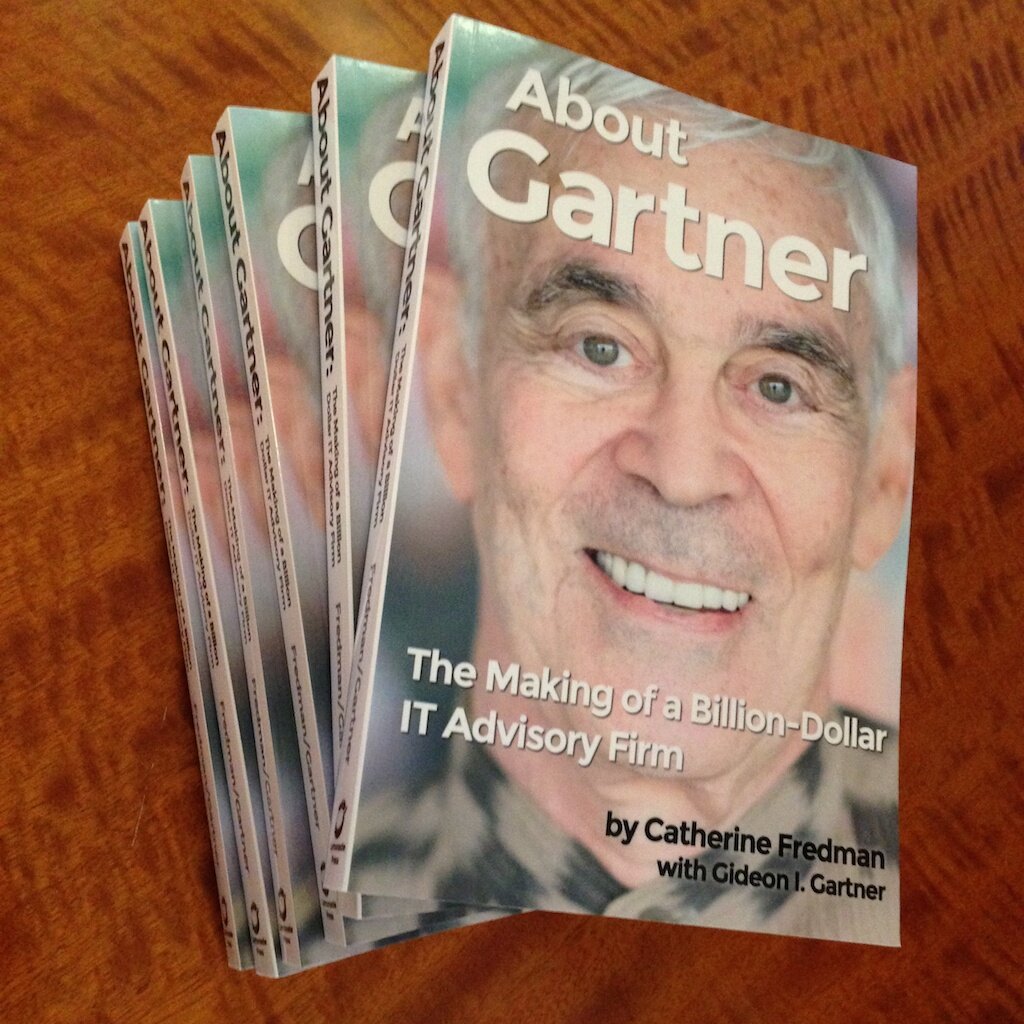

Soundview was now gone, the tragic story of a rather unique firm which I founded, which at first capitalized on its tight relationship with the arguably most influential international source of IT information and advice (Gartner Group), full of brilliant analysts, growing like a weed with potential to become a major boutique firm, and then falling apart as a result of poor top-level decision-making.

I don’t enjoy criticizing managements, but being the firm’s founder I can hypothesize possible errors which if avoided might have contributed to a more positive ending:

1. Face to face interactions with Gartner analysts were designed to be for Soundview’s benefit; aside from its analysis Gartner was a major source of important information tidbits during personal encounters between analysts of the two firms, a source arguably more valuable than from published reports. When Soundview moved out of its Gartner space in the late 1980s, although it remained in the same office park it was a bit too far away from the Gartner analysts; the firm should have negotiated a deal with Gartner, leaving at least a few key analysts in the main Gartner building where analysts were housed. Did Soundview management recognize the value of tight personal connections with Gartner’s large and high quality analysts? Wasn’t this the primary reason for Soundview’s differentiation?

2. A second example of possible lack of management focus on its differentiators compared with competition, let alone not fully exploiting the Gartner relationship: most Gartner research notes had at least some indirect financial implications regarding IT vendors, so every piece of Gartner written output could have been reviewed professionally by a trained Soundview specialist in order to extract any and all financial implications at very low cost. And the firm might have encouraged its analysts to call the Gartner author for explication when feasible (I believe these rights were documented when Gartner Securities was spun out). But Soundview was doing fine at the time, and it was perhaps becoming sloppy.

3. Lucky for Soundview, Gartner never implemented its own right to give 6-months notice in order to market our own research to Wall Street rather than passing it on to its divorced child, especially after the two initial board members and I capitulated and sold our equity interests to it, and after we noticed that Soundview significantly reduced its dependence on our work. Ours would have been a smart move, recreating the attractive deal which we originally had with Dillon,Read with an established broker-dealer partner as our marketing arm in the financial technology space. I was too busy to pursue such a tack, but Soundview should have sought additional research relationships in sectors other than technology. Even the expert network Gerson Lehrman which was founded around the same time as Soundview would have been a natural partner (Wall Street today is quite expert-oriented in obtaining valuable inputs, the advantage being that literally thousands of experts, covering every niche in most large industries, are available for interactions). But Soundview may have stuck to its original and narrow scope for too long.

4. In fact, Soundview might have negotiated a new deal with Gartner itself, which had hundreds of analysts to Soundview’s 15-30, where it would pay Gartner even a nominal sum each time its analysts were asked to and spoke directly with Soundview’s Wall Street clients. Who was supposed to be doing thinking along such lines?

5. Along the same lines, Soundview’s reputation as the top source for institutional investing advice in many sub-sectors of the tech market, would have been worth a small fortune to those large brokerage firms which were relatively weak in technology research. In fact, J.P. Morgan offered around $250 million to purchase Soundview, and in cash! I do not know how the decision was made to sell Soundview at all, given its rapid growth. But was there sufficient due diligence re the eventual purchaser Wit Capital? Did Wit have much of a track record (it had little)? Was the decision to accept stock with a lock-up compared with a lesser amount of cash from J.P. Morgan discussed with qualified external sources? The decision to sell must have been based in part upon the weak economic forecasts, and if so would one really wish to accept locked-up stock instead of cash? Was there open debate internally on these issues? I do not feel guilty for effectively dis-involving myself with Soundview after 1985 to the extent I did. When the firm’s President asked me along with others to sell my interest back to the firm, I considered asking for a deal where I’d be a more active chairman; not that I would have (or could have) driven Soundview’s decisions; by 1987 I had zero say in its management and was overburdened at Gartner, however this financial company meant a lot to me because it had been my baby and when it grew above $50 or $75 million in revenues I would likely have urged that it attract a heavyweight senior executive from Wall Street. At least in retrospect, Soundview likely required a survivor of past Wall Street crises to manage its growth and overall diversification strategy. After all, the issues that arise in many organizations during rapid growth (while expanding its scope of operations simultaneously), create huge executive demands. Unfortunately Soundview’s professional staff had little experience managing large and complex organizations. I’d like to know if any responsible 10-year-old firm (let alone 20), with even $50 million in revenue (let alone Soundview’s $150M), would not regularly audit its governance strengths and weaknesses!

A top executive assessing this full-service brokerage firm (research,trading, and sales, in the complex technology space) would likely have recognized that the firm was sufficiently profitable and respected that it might have done much better in diversifying itself into serious banking for small technology firms. A judicious transformation towards the likes of Hambrecht, Needham, Montgomery, Robertson Stephens, et al, seems to have been in the cards.

Observers differed in their assessment of Soundview’s future: some thought that since the company never really had senior, savvy, and experienced Wall Street management, its best end game would have been the rumourded sale to J.P. Morgan for $250 million cash. The company had ridden the tailwind of the technology bubble and might have failed (low probability) on its own even without Wit, since it had not continued to build any real competitive advantages through the kind of constant tinkering with its model, as Gartner had. And instead of its infatuation with high fixed cost and highly variable banking, it might have invested much more in money management, both institutional as well as retail! It under-leveraged its brand, it could have had a family of mutual funds in technology and other high growth industries, open and/or closed end funds that would likely have created a recurring revenue stream. Jaimie Townsend gets credit for building up the trading/sales capacity but ultimately, management sold out by investing in banking and allowing the relative weakening of its competitive edge in research ( the “edge” originally provided by Gartner) but which was now virtually gone.

In summary it may be 20/20 hindsight but there seems to have been one overriding omission and one overriding commission: the omission was in not ever appointing an outside board to provide helpful or essential counsel; the commission was in selling Soundview to Wit Capital for locked-up stock when the economic handwriting was on the wall.

An after-note by Arnie Berman:

SoundView was a terrific place to work that was managed by people that were keenly interested in serving the best interests of its customers and employees. In hindsight, the firm could have grown to an even larger size than it did if it was managed by people with greater experience. When Wit offered to buy SoundView at a ridiculous multiple of its book value, SoundView’s partners were keenly aware that the price tag was so elevated because we were being paid in what I called “Internet psycho wampum.” However, we rationalized this exposure by noting that even if Wit’s stock fell by 50%, we would still be way ahead. None of us dreamed that the share price would instead decline by 90%! One reason the partners were attracted to this deal is that the buyer wanted all of us. They wanted all SoundView employees in research, sales, trading, banking and in the back office to part of the combined entity. Other buyers would likely have eliminated many jobs – or entire departments. In retrospect, Russ can be criticized for agreeing to sell to Wit instead of selling to JP Morgan, Keefe Bruyette or some other bidder. But I believe this decision resulted from a desire to do right by all of SoundView’s employees.

48 Comments